Pop and Click

Or, how Andy Warhol learned to stop worrying and love the personal computer.

On June 14, 1985, Andy Warhol wrote in his diary that he had a meeting with Commodore about becoming a spokesperson for its home computers. “I guess I got the job,” he wrote. “I was afraid that they were going to put a spotlight on me and have me draw in front of 700 people, but it was okay.”

Not so fast, Andy: A little over a month later, Commodore pretty much did that. On the night of July 24, a tux-wearing company exec waltzed onstage at the Lincoln Center in Manhattan for the ultra-dramatic debut of the company’s Amiga computer. “What you are about to witness is the result of an effort of research and engineering that began in 1982 and which to date has consumed over 100 man-years of engineering talent,” Robert Pariseau gushed.

Later in the evening, Warhol and Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry were introduced to the crowd, and Warhol was prompted to use the new machine to ‘paint’ Harry’s portrait. As an Amiga artist narrated the whole scene, Warhol used its ProPaint program to fill in the background behind a photo of Harry, before coloring her hair a vibrant yellow. The result is charmingly low-tech in retrospect — and also reasonably comparable to some of Warhol’s famous screen-printed portraits.

The audience seemed delighted, but Warhol was less thrilled with… all of it. “Went along and the drawing came out terrible and I called it ‘a masterpiece,’” he wrote in his diary. “It was a real mess.”

Despite being initially underwhelmed, Warhol continued to experiment with ProPaint, and created a number of digital works on his Amiga, including a short film based around news footage of Marilyn Monroe, sketching in a third eye on “The Birth of Venus,” and — of course — drawing a Campbell’s soup can.

After Warhol’s death, his Amiga computers and over 40 accompanying floppy disks ended up in storage at Pittsburgh’s Andy Warhol Museum. In 2011, artist Cory Arcangel learned about those disks, and reached out to the museum to see if, you know, they’d ever checked to see what might be stored on there. After learning that the archivists had never attempted to access any of Warhol’s Amiga files, Arcangel worked with the Computer Club at Carnegie Mellon to see if there was any way to look for — and recover — anything that the artist might’ve saved.

According to the Computer History Museum, after two-plus years of determining the best practices to access the historically significant files, they were finally able to recover 18 small artworks from the long-obsolete disks. Those pieces — many of which include his digital signature — are some of the last works that Warhol finished before his death.

“What’s amazing is that by looking at these images,” Arcangel said at the time, “we can see how quickly Warhol seemed to intuit the essence of what it meant to express oneself, in what then was a brand-new medium: the digital.”

Warhol’s computer, graphics tablet, and prints of his Amiga art have since been displayed at the Andy Warhol Museum. That would’ve been a cool end to the story, but because we’re living through the Worst Timeline right now, five of those pieces were put up for sale as NFTs in 2021.

We’d love to know what Andy would’ve written in his diary about that shit.

A version of this story appeared on the news page of Questionist’s parent company, Geeks Who Drink.

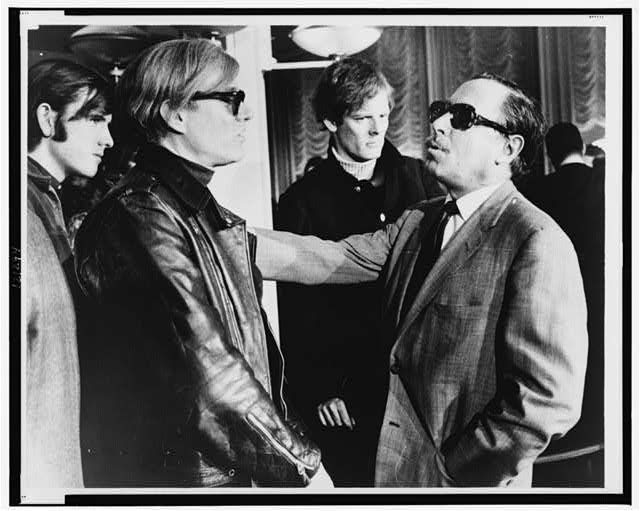

Inline image: James Kavallines, via Library of Congress.